In the bonafide phenomenon that is “Heated Rivalry,” no interview with the stars or series creator Jacob Tierney can escape one question: why women would flock to a series about the turbulent romances of gay hockey players.

Truth is: For those of us who consume anime and manga, the breakout success of “Heated Rivalry” isn’t a surprising cultural development at all. Long before the “Heated Rivalry” series premiered on HBO Max in November, the story existed as two novels from the popular “Game Changer” series by Canadian author Rachel Reid. It exists in the queer romance space overwhelmingly written and consumed by women — sometimes queer, often straight.

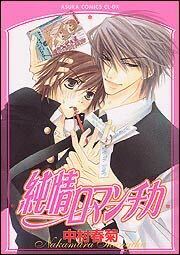

However, the book (and the show’s) narrative stylization echo Japan’s decades-old manga genre Boys’ Love. Also known as BL, or Yaoi, it’s written by women, for women. A niche category with an outsized cultural influence, it’s known for its ability to explore and experience sexuality via narrative without a female presence.

We’ve seen this phenomenon in American media before, such as the U.S. adaptation of “Queer as Folk” (2000-2005), which intrigued a majority-female viewership with its chronicles of modern gay male life. Anne Rice’s “The Vampire Chronicles” is another example of queer male narratives written by women; look at the online audience discussing its current AMC adaptation and the vast majority of its most avid fans are female.

Still, understand how Yaoi treats authorial perspective and queerness and you’ll understand what feeds the fandom of “Heated Rivalry.”

Boys’ Love dates back to 1970 with the publication of “Sunroom Nite.” It spread through self-published fan works (known as dōjinshi) and its popularity grew during the mid-’90s. Like many genres within the Japanese media umbrella, it refers to both its target audience and its subject matter.

Traditionally, BL are romance and love stories between men that are written primarily by women and have a core audience of female readers. Japanese gay stories made by gay men for a gay male audience are typically referred to in Western circles as Bara. (There’s also a lesbian genre known as Yuri, which has a more flexible relationship with demographics).

Questions of authorial identity, and whether it’s appropriate for a queer story to be told by straight writers, are murky and controversial; it feeds much of the criticism surrounding epic best seller “A Little Life” by Hanya Yanagihara.

BL, in its feminine perspective of homoerotic male relationships, offers a fascinating case study of this phenomenon. Many entries in the genre exist in the uncanny valley between heterosexuality and queerness, where a relationship is gay because of the physical absence of women more than the actual identities of the lovers.

A frequent trope in these romances is the men in love don’t identify as gay; often these are the only men for whom they’ve ever had romantic feelings. Sex scenes in these manga are often mocked for their unrealistic positions and content; there’s an entire Wikipedia page for the fan term “yaoi hole.” However, the defining cliché of Japanese BL is the Seme and the Uke, character archetypes that subtextually gender ostensibly same-sex relationships.

Seme is, bluntly, the top in the traditional BL relationship. A typical Seme is older, taller, and more muscular than his romantic interest, and is defined by dominance and sexual aggression (emphasis on aggression: notoriously, many BL love stories begin with rape or otherwise dubious consent that eventually morphs into true love).

The Uke is the bottom, and is written in a way that codes him as female: he’s shorter, thinner, pretty to the point that he may be androgynous, sexually inexperienced, shy, and emotional in a way that borders on histrionic.

Frequently, there’s an unstated power imbalance that places the Seme in a position where he’s “wooing” the Uke. It’s an extreme heteronormative portrayal of gay relationships where the couple is essentially straight in all but aesthetics.

Reading BL as a gay man is generally not about seeing yourself reflected in the story. Unlike other queer male media, it’s a female-centric fantasy that imagines a functionally heterosexual relationship between two men.

So where’s the appeal in that? Scant academic studies echo many of the interviews with Tierney and his cast: For female readers, there’s a sense of safety in being removed from the sex and romance they consume; they also enjoy a relationship removed from the power dynamics of gender. Women have limited physical presence in BL media, but they’re spiritually represented in the genre’s tone, perspective, and who is meant to derive sexual pleasure from its contents.

For anyone who wondered why “Heated Rivalry” fans say they’re “fujoing out” on Twitter, that’s a takeoff of the BL term “fujoshi,” a pejorative roughly translating to “rotten girl” now reclaimed by female fans of queer male-centered works. South Korea, China, and Thailand also have developed their own live-action BL industries.

The “Heated Rivalry” universe has its roots in fanfiction, a genre that takes obvious inspiration from BL tropes. Reid’s first novel “Game Changer,” which focuses on the characters Scott and Kip, notoriously began life as a fanfiction about Captain America and Bucky Barnes from the MCU and was later retrofitted into an original story.

“Heated Rivalry” is the second in the six-book series and was the most popular by far, even before the show’s release. It does not have an explicit fanfiction counterpart, although the characters of Shane and Ilya take broad inspiration from the real-life rivalry between star hockey players Sid Crosby and Alexander Ovechkin.

But, more than other books in Reid’s series, “Heated Rivalry” and its love story slide neatly into many BL genre conventions.

Given the differences in Western and Eastern beauty standards, and the realities of setting a romance in the hockey world, neither Shane nor Ilya fit the mold of BL’s feminine, willowy bishonen. All the same, both men fall neatly into stereotypical Seme and Uke roles that in some ways gender them despite their masculine appearances.

Notably, they’re rigid about the sexual roles they take in their relationship. Reid’s other books feature couples willing to switch it up (the most interesting part of the largely tedious “Game Changer” novel is smoothie-maker Kip’s shock when the macho Scott asks to bottom the first time they hook up). Shane and Ilya, on the other hand, are strictly bottom and top. While this dynamic does reflect some queer relationships, it also carries connotations of one partner occupying a more “feminine” role — an idea the book’s characterization reinforces.

Ilya fits the basic character traits of many Seme found in BL stories: Sexually experienced and confident, he pursues Shane while his bad-boy image hides a heart of gold. Shane is not particularly feminine in his presentation but his behavior and thoughts align with the Uke archetype: He’s shy, has never been intimate with another man, is socially awkward and insecure, and is more emotionally open and sensitive than Ilya.

In the the book, Shane’s thin characterization can make him come across as a self-insert for female audience members. A scene late in the novel reads extremely straight: As he watches Ilya play with children, Shane wonders if his lover will want kids.

Reid’s writing leans into a stark physical dichotomy between the two men: “Rozanov was so… masculine. Shane was baby-faced and short, and couldn’t grow proper facial hair, and barely had any chest hair. Rozanov was almost exactly the same age as him, but he looked like he had crossed over a magical line to adulthood.” She often highlights the physical differences between the two, with the height gap frequently referenced during sex scenes.

Uncomfortably, this is also how the novel explores Shane’s racial identity. Neither the “Heated Rivalry” book nor its sequel, “The Long Game,” puts Shane’s half-Japanese heritage in the context of his career in the NHL (a league that is roughly 90 percent white) or how it informs his experiences as a gay man. His ethnicity seems only to create an aesthetic difference that codes him as the more feminine of the two.

Much of this applies only to the “Heated Rivalry” book; even in “The Long Game” sequel, Reid softens Ilya considerably and complicates the couple’s dynamics in ways that largely avoid Seme/Uke characteristics. The TV show hews faithfully to the original text in plot and dialogue but often makes significant tonal departures, with the added perspective of writer/director Tierney (an openly gay man).

Casting plays a big role: Hudson Williams (Shane) and Connor Storrie (Ilya) are two men of roughly equal height and build. The writing emphasizes a light dom/sub flavor in their relationship that Reid’s book never really identifies — for example, Shane roleplays a bellboy in a forced-seduction fantasy with Ilya in the final episode — and provides texture that considerably levels the relationship’s playing field.

Shane particularly receives many narrative and performance additions that push him out of the thin Uke stereotype. Williams’ active choice to play him as being on the autistic spectrum recontextualizes his shyness and inexperience (Reid said she supports this, but didn’t actually write him as such). That reorientation helps make his relationship with Ilya feel like that of… well, that of two adult men. In the source text, Shane acts like an awkward teen well into his twenties.

That’s not to say the “Heated Rivalry” show is “elevated” compared to Yaoi; it retains the characteristics of the genre consumers have loved for years, including a dramatic but ultimately sweet romance and sex scenes between men ultimately intended for female pleasure. Only here, it’s made more relatable for the gay male audience it’s about. Bingo: a massive global following.

Just don’t call what the show is doing with its female audience new or unexpected — if there’s a lesson to learn from manga, it’s that women have been “fujoing out” for generations.

Season 1 of “Heated Rivalry” is now streaming on HBO Max.