How chatbot-first thinking makes products harder for users

We’ve lived with AI long enough to witness some groundbreaking changes in how we live, work, and design. But we’ve also lived with it long enough for misconceptions to emerge — before best practices have really had a chance to settle.

The pace of disruption remains wild. However, 2026 is already being described as the year of AI fatigue.

For product leaders, this creates a new challenge: we need to define ways to approach UX for AI without making AI-powered products exhausting, inconvenient, risky, and unsustainable.

This article focuses on one of the widespread misconceptions that could send the future of UX along a very wrong trajectory. I call it chatbot-first thinking: the assumption that conversational interfaces can — or should — replace most existing UI patterns completely.

The Promise of Zero UI

Let’s start with the most obvious question on the surface:

Is the future of user experience purely conversational?

For many, it’s tempting to dream about it. Especially if you’re a frequent user of large LLM interfaces today. Especially if you follow announcements like OpenAI’s recent promise of a screen-free, pocketable product that hints at a life increasingly driven by AI orchestration. And especially if your mental model of AI experience is based on the early ChatGPT experience, which was entirely conversational, with no UI snippets and micro-apps within the chat dialogue.

It’s also easy to fall into this line of thinking after watching the rise of ChatGPT apps — pulling familiar services, like OpenTable, directly into the chat dialogue (spoiler alert: you still need to visit OpenTable’s website to complete your user journey, as is the case with almost every app in the ChatGPT app directory). The idea that everything could eventually live inside a single conversational interface starts to feel not just plausible, but inevitable.

https://medium.com/media/c1daf7b9a5b088348fa7d2943f70612d/href

In my personal life, as an enthusiast of AI tools, I increasingly try to experiment and outsource tasks to LLMs via text or voice. Agents from tools like ChatGPT or Claude — despite being clumsy, slow, and often struggling with all the still-non-AI-first websites — can handle a variety of scenarios, all of which I can trigger via a voice command in the chat.

But there’s only so much I can do via text, let alone voice.

Can we always use conversational UX?

The reality is much more complex. Many of the tasks we deal with in our personal life and at work require rich, multi-modal interaction patterns that conversational interfaces simply cannot support.

If you’re a product leader evaluating whether UX of your AI functionality should become purely conversational, I recommend thinking twice whether it will become an accelerator or a blocker for your product.

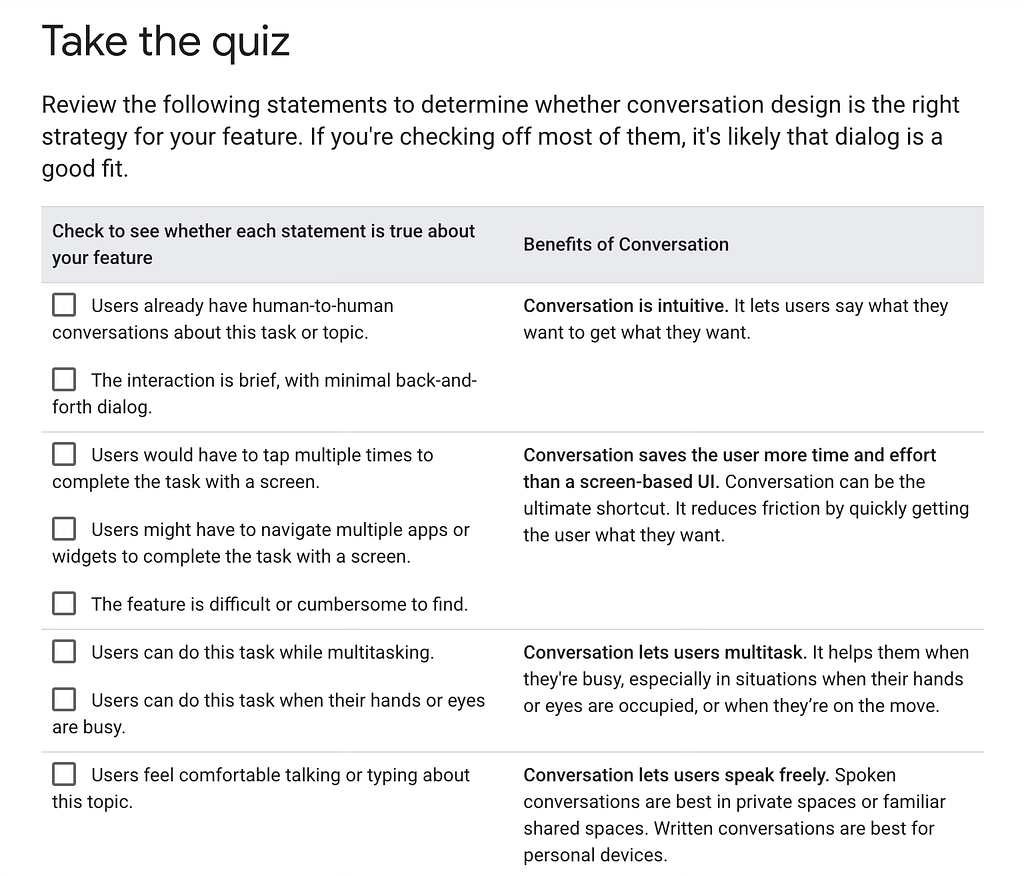

One of the good starting points is Google’s checklist for the conversational approach fit:

When working with clients, we take this evaluation to the next level by guiding them to the interaction pattern choice via a series of validating questions, and essentially checking — does the conversational approach check all the boxes?

Question 1: Is it accessible?

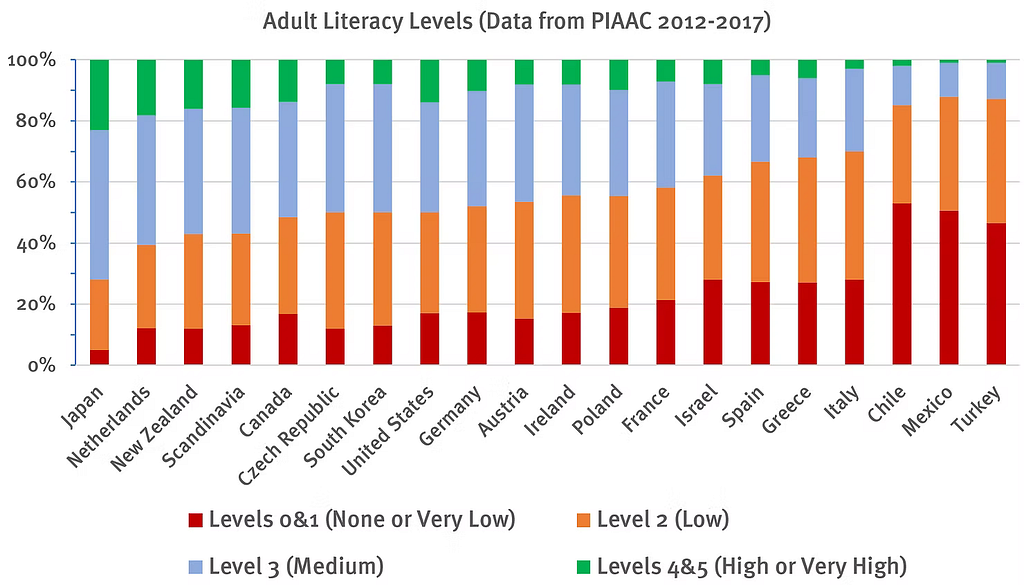

Chat-based interfaces require users to describe their problems in written text. Recent literacy research shows that nearly half of the population in wealthy countries struggles with complex texts and won’t get good results from chatbots. Jacob Nielsen called it a fundamental usability problem, because it forces users to become prompt engineers just to reach the same basic level of user experience that visual interfaces previously provided.

Question 2: Does it promote the product’s adoption and discoverability?

Let’s imagine all of your product’s users are articulate enough. Could they still use a conversational approach for virtually everything?

Consider food ordering as an example. Major players in the AI industry like to paint a future where ordering a lunch delivery is as simple as issuing a voice command. But what if you don’t know what you want to order at all and would prefer to see the menu first? Listening to a menu, when it could be presented via graphical interface, violates one of the core usability principles, “recognition rather than recall” which advises minimising memory load by keeping interfaces self-evident.

Unlike a screen, spoken commands and outputs vanish instantly, giving users nothing to refer back to. It’s “much easier to pick out the desired item from a list when the list is displayed on a monitor than when it’s read aloud,” as Jacob Nielsen explains.

Back to our example with food ordering: how often do you actually spell out the names of your favourite food items in your head when you’re hungry? Maybe you just don’t remember the quirky name of that rice bowl you always order. Which leads us to the next issue with conversational interfaces.

Everything we put in a chat prompt is a piece of context, and the result of our collaboration with a chatbot can be only as good as the precision and relevance of our input. Therefore, prompt-based products work best for the users who already know how to ask the right question.

In a purely conversational system, users often don’t know what features or commands exist, unless they actively ask or the system hints at them. Moreover, when they do discover the product capabilities and get their job done successfully via chat, how can they be sure they can still get the exact same result next time? Generative AI is probabilistic by nature, and the results may differ slightly each time. Of course, building a knowledge graph, templates, or guardrails can reduce this variation — but it can never remove it entirely. Conversational interfaces are a poor fit for high-precision tasks — unless they are heavily supported by non-conversational structure.

Question 4: Is it reliable?

Imagine a business user using a purely conversational assistant to update a contract term: “Change the renewal period to one year and apply the standard discount.”

That sounds clear to a human, but in practice it leaves room for interpretation. Which contract version? Which definition of “standard”? Does the discount apply immediately or at renewal? Is it one year from today or from the original start date? Small variations in phrasing — or in how the model interprets context — can lead to different outcomes each time.

In high-precision scenarios like this, users need to see exact fields, values, and constraints, review changes side by side, and explicitly confirm what will be saved. A conversational interface can help guide the process, but relying on chat alone makes the experience fragile.

Question 5: Is it necessary?

Just because a task can be done via chat, should it be done via chat?

Let’s take an example of an atomic, well-defined task that looks like a textbook success case for an AI agent: I recently needed a transcript for a YouTube video and decided to outsource the task to the ChatGPT agent.

The old way of doing it:

- Search for an online transcription service

- Copy and paste the YouTube link

- Click a call-to-action button

- Download the transcript

The new, agentic way of doing it (as of January 2026):

- Prompt ChatGPT: Get me the transcript of this YouTube video (link included)

- (Optional) Observe how the agent navigates across multiple third-party transcription services, struggles with permissions, cookies, paywalls, or rate limits, retries failed requests, reformats output several times, takes minutes to complete the task but finally provides the transcript

- Download the transcript

If I need the transcript now, the experience quickly becomes frustrating. But it’s not just that.

Question 6: Is it sustainable?

The described experience raises another debate. When an LLM agent spends five minutes crawling the web, calling tools, retrying failures, reasoning through intermediate steps, it is running on energy-intensive infrastructure, contributing to real data-center load, energy usage, and CO₂ emissions. For a task that could be solved with less energy by a specialised service, this is computational overkill.

From a systems perspective, this isn’t just inefficient UX — it’s inefficient infrastructure usage. The question becomes: was AI the right tool for this task at all?

But what about agentic experiences? Won’t they remove the need for UI (and UX)?

First, let’s explore what an AI agent is.

An AI agent is a software system that autonomously pursues goals and completes tasks on behalf of a user by reasoning, planning, and acting across tools and environments with minimal human input.

The agent’s role is to support human workflows: making information visible or drawing attention to what matters, handling parts of the workflow, exploring alternative scenarios, suggesting a best-guess next step, translating intent into actions by interfacing with APIs, coordinating signals across systems, or executing commands. The human remains the primary problem solver, with the agent augmenting and supporting — not replacing them.

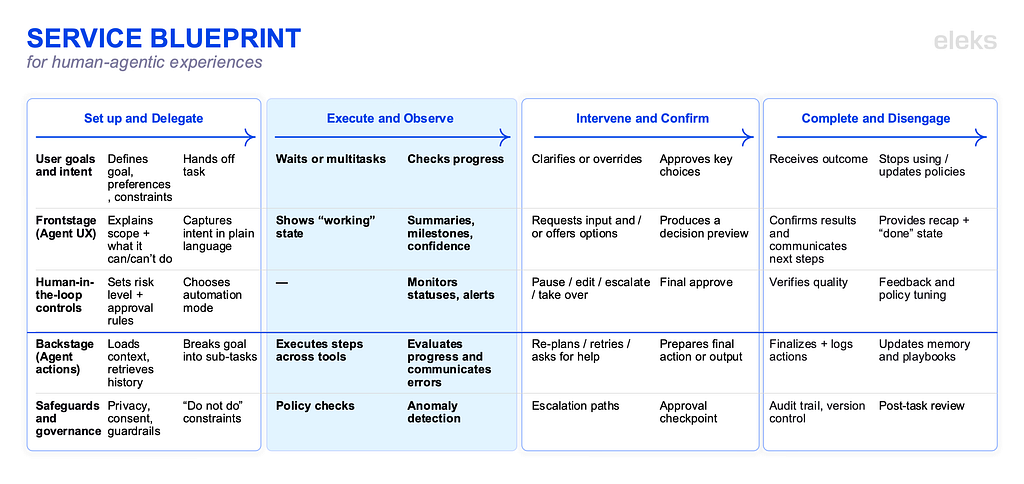

In line with service design thinking, agents need humans to support them across several stages of the agentic lifecycle: 1) Set up → 2) Delegate → 3) Execute → 4) Observe → 5) Intervene → 6) Confirm → 7) Complete → 8) Learn and Disengage. This system layer is called human-in-the-loop (HITL) and is intended to ensure accuracy, safety, accountability or ethical decision-making of AI workflows.

Agentic experiences require a service design approach to mapping and designing of these novel, dual experiences where agents and humans collaborate to achieve results we earlier could only dream of.

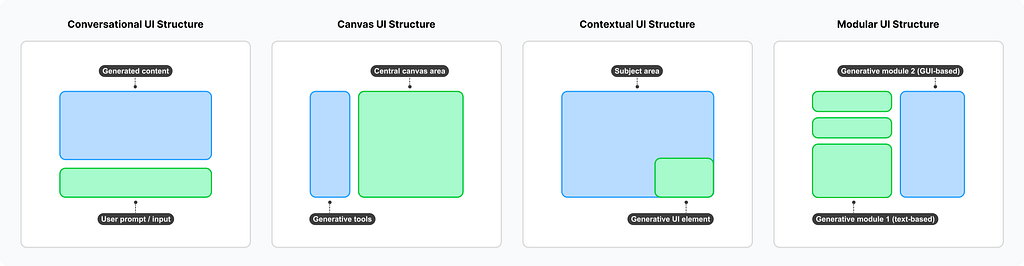

All of the described stages and touchpoints require choosing from a variety of interface approaches, beyond just the conversational one (canvas UI, contextual UI, modular UI, simulation environment, and other types). But this is a topic for a different article.

The price of (not) doing UX for AI the right way

Customer fatigue with AI slop is growing across all industries, with business initiatives like AI-generated ad campaigns triggering massive online backlash.

In 2024 LinkedIn silently removed the shallow and unhelpful AI prompt suggestions in the feed which were spotted frequently by Premium users. Meta was also criticised for rolling out Meta AI as a default part of the interface in their major apps, such as in the search bar or with prominent icons users can’t easily remove. Despite the user backlash, Meta is continuing to push AI features and earning the reputation of a company that is leading with AI for AI’s sake and hurting user experience rather than helping it.

On the other hand, companies that apply user-centered approach to the design of AI-powered products are enjoying success as pioneers setting new mental models.

For example, Microsoft 365 Copilot’s success with 70% of Fortune 500 companies is partially explained by their inline-style interaction pattern which has become the baseline of intuitive AI UX — the one that enhances existing workflows, not replaces them with inferior interaction patterns.

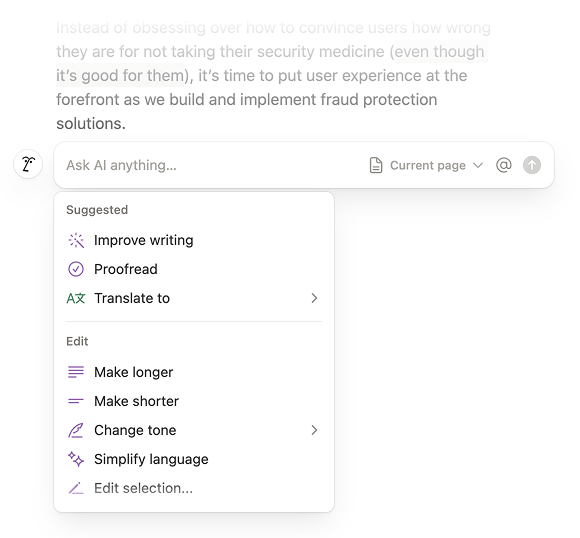

Notion AI has been one of the first companies which enabled the interaction pattern of AI suggesting contextual preset actions. This is just one example of how thoughtful selection of a UX pattern can remove the cognitive load of wondering what the AI can actually do with the text and what the best way to prompt it is.

The future of UX for AI will not be a single interface or interaction pattern — it will be layered ecosystems of tools, touchpoints, and safeguards. As these ecosystems become more agentic, the need for thoughtful UX design only increases.

This is where user-centered design and service design become essential — not as supporting roles, but as foundational disciplines. UX and service designers are uniquely equipped to map end-to-end journeys, identify moments where human judgment must remain in the loop, and design systems that clearly communicate intent, limits, confidence, and accountability. They help answer the hard questions that AI alone cannot (at least not in its pre-AGI era): When should the system act? When should it pause? When should it explain itself? And when should it step aside entirely?

If there is one lesson we should take from the last decade of digital product design, it’s that technology rarely fails because it isn’t powerful enough. It fails because it isn’t shaped around real human needs and contexts. AI is no exception — and the cost of getting it wrong is significantly higher.

Recommended further reading

When Words Cannot Describe: Designing For AI Beyond Conversational Interfaces by Maximillian Piras

State of UX 2026: Design Deeper to Differentiate by Nielsen Norman Group

Common AI Product Issues by Luke Wroblewski

The Articulation Barrier: Prompt-Driven AI UX Hurts Usability by Jakob Nielsen

AI: First New UI Paradigm in 60 Years by Jakob Nielsen

Survey of User Interface Design and Interaction Techniques in Generative AI Applications by Reuben Luera

The Hidden Cost of Instant Answers by Saleh Kayyali

Survey of User Interface Design and Interaction Techniques in Generative AI Applications by Reuben Luera

Human-in-the-loop in AI workflows: HITL meaning, benefits, and practical patterns by Juliet John

How AI Agents Are Reshaping the Internet from Human-Centered to Machine-Mediated Commerce by A. Shaji George

Are we doing UX for AI the right way? was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.